The history of media monetisation

You know the deal: you want to read about the latest horrifying global event, so you click on the first link, and… it’s paywalled. You go back and click on the second link. Also paywalled (and screaming at you about your ad blocker). Onto the third and fourth articles. Eventually, the global conflict has resolved itself before you find out what the hell is going on.

This is just one symptom of a much larger and more complicated problem: media monetisation. Most of the global media industry is bleeding money and has been disrupted almost beyond recognition. So, how did we end up here? Where are we going? Who broke this system, and how can we un-break it?

I may not have all the answers, but I definitely have a lot of questions.

What is media monetisation?

First, let's establish a baseline. What is media monetisation? Media monetisation is all about who pays for the media and why. Because the media and entertainment industry is valued at a global $660 billion dollars annually, this is an incredibly large, nuanced, and complicated subject. But it’s also a very important one, because the media doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Public opinion and global policy are shaped by the media that people consume, and biased media can have life and death consequences.

Media bias is one of the biggest side effects of this monetisation question, because as the adage goes, if you aren’t paying for it, you’re the product.

Who is paying for the media you consume, and why are they paying for you to consume it? Why would these individuals and corps spend millions, if not billions, getting their perspectives in front of your eyes? Is it possible for media to be unbiased at this point, or are we, as consumers, just expected to unquestioningly consume whatever media is most ideologically aligned with our existing viewpoints? Is this healthy, or is it just further radicalizing and entrenching people in their echo chambers?

Media monetisation is a huge issue. But it didn't used to be. And it doesn’t have to be. Before we can realistically talk about what the media could look like in the future, let’s first look at where we’ve come from.

The history of media monetisation: from the 1600s to now

The legacy of digital media history is far more nuanced than I can cover in one article. However, having an overview of history will establish a starting point to talk about how media monetisation has evolved up to the present day.

Pre-newspapers (pre-1600s)

Before printed newspapers, most news was dispersed through word-of-mouth, town criers, or bulletins in city squares. This method was inefficient. Maybe you heard that your lands were being overtaken by some neighboring empire beforehand. Perhaps you found out when an army was knocking at your door and setting your roof on fire. Either way, the news dissemination was slow, chaotic, and rife with human error, fake news, and mistranslation (kind of like how Facebook is now, if we think about it).

Early newspapers (1600s–1700s)

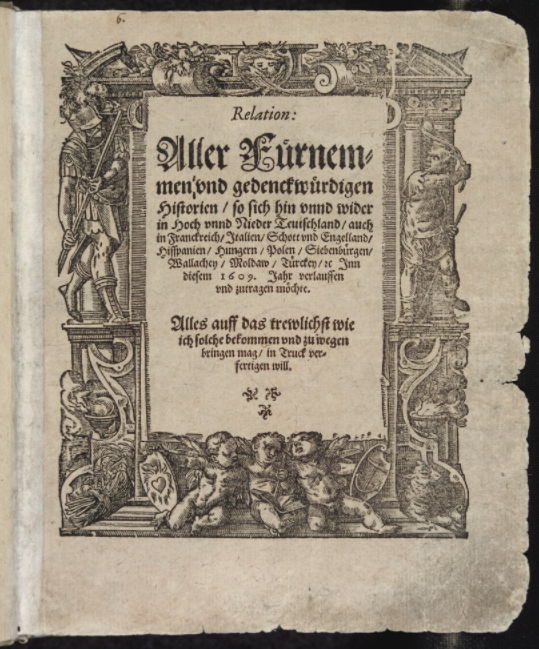

With the invention of the printing press in the 1450s, mass media was on the brink of becoming a real possibility. By the 1600s, newspapers were popping up throughout Europe, with the Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien first circulating in 1605. This was thought to be the first bona fide newspaper, but others quickly started circulating worldwide.

Something you may not know if you personally do not own a 1600s printing press, but they are expensive and extremely annoying to operate. The average media consumer did not have a ton of fun money sitting around to invest in print media. So, early newspapers were often funded by political institutions and governmental bodies, and aimed more towards wealthy elites.

Because corruption and propaganda are not new concepts, these Ye Olden Timey papers were often more tools of the state than actual, unbiased news. Think about it: what incentive does a governing body have to be objective when they are the ones paying for the information that is being disseminated? That was a good question in the 1600s and it remains a good question now.

Advertising (1800s–1900s)

The earliest newspapers didn't really have an infrastructure for advertisements. Not that they necessarily needed to, because they were basically propaganda rags. In the 1800s, newspapers realized that they could both propagate and profit through newspaper advertisements. Display ads started popping up to offset the costs, and are still prolific today in both digital and physical media formats.

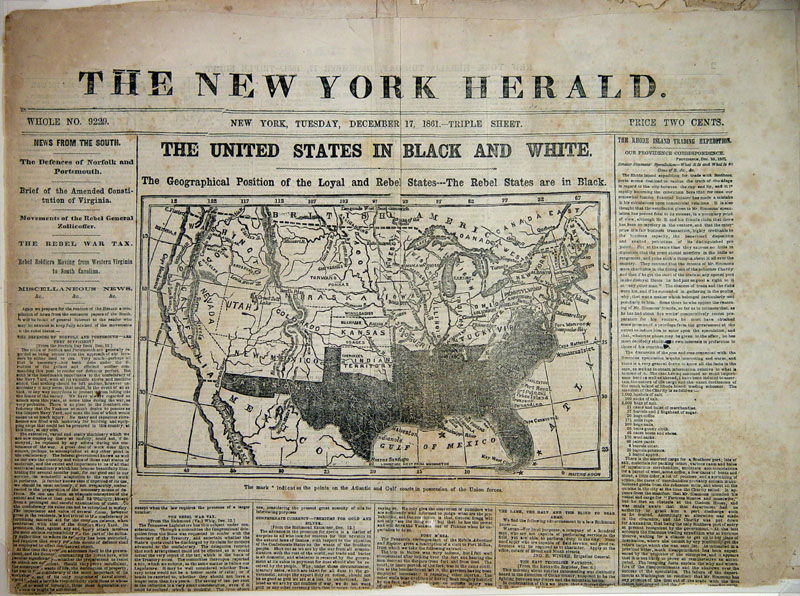

The 1800s saw newspapers becoming increasingly prominent in society. Literacy started going up, as did newspaper readership and advertiser revenue. It turns out that being able to read the ads directly correlates to their efficacy. The “penny press” news began being circulated in 1830, which made for much cheaper papers, offset by ads and available to even the average person.

Subscriptions (late 1800s–present)

The late 1800s also saw a rise in the subscription model of print media. Folks could sign up for a regular subscription and receive a copy of the paper regularly delivered to their homes. This model existed as the status quo news model for a very long time and still exists today, but has largely moved online, where websites paywall the news behind a subscription model.

Subscriptions ensured that people got the news, whether they wanted it that day or not. This has become a standard practice and revenue generator for media all around the world ever since. Subscriptions, advertisers, big interest donors, and lobbyists all work in tandem to make the rapidly globalized news system function, and regular subscriptions act as a stabilizing force for small newspapers and large media conglomerates.

Classifieds (early 20th century–2000s)

While classified ads have technically been around since the mid-1700s, they only took off in the early 20th century. But once they did, boy, did they take off. Businesses and individuals alike were able to pay a small fee to list their offerings and find buyers and customers. There were even personal ads that acted as the analog Tinder and job-posting advertisements that served as the OG LinkedIn.

Classified ads were a brilliant move. Newspapers could help connect people with a broad readership that wasn't available before the internet, and they collected a monetary fee for every single ad posted. The classified ads section was often pages long, with all those classified ads acting as additional revenue for the newspapers. It's hard to adequately articulate exactly how important classified ads were because they fell out of favor so dramatically, but classifieds were massive revenue generators for newspapers, often accounting for up to 70% of their total revenue.

Eventually, classifieds were overtaken by more modern approaches, like Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace. Craigslist and, to a lesser extent, sites like eBay acted as massive industry disruptors, devaluing the newspaper industry by billions very rapidly. You'd be hard-pressed to find a bona fide classified ad these days, and the annual revenue of classifieds dropped 92% from 2001 to 2011 (and it’s only continued to decline).

Digital advertising (1990s–present)

As newspapers went online, so did their ads. The transition was inevitable as more people joined the web. In a lot of ways, this was a good thing. Environmentally, a lot less paper was wasted. The news could also travel faster and update more frequently, which in theory meant more accurate information. (Oh what fools we were.)

However, many terrible things also happen to the media industry. Local news started dying, with over 2,200 local newspapers closing from 2005 to 2021 in the States alone . Classified ads started disappearing (as previously mentioned), and people began canceling their print subscriptions. This was the death knell for many small, local, independent news outlets.

Ad blockers were another significant blow for the industry as news outlets attempted to subsidize a loss of classified and print ad revenue. If you’ve ever been on a news website without an ad blocker, you’ll know it’s quite the experience.

The move to digital has been devastating for newspaper revenue. Even without a paywall, a print reader is worth 228x more than a digital reader. News outlets everywhere had to aggressively cut back on their more expensive content, like investigative pieces, in favor of smaller, more digestible, more reactive media. Ads were everywhere and ad blockers cost potential revenue to the tune of tens of billions per year (not just for news outlets, but definitely also for news outlets).

Paywalls (2000s–present)

The early 2000s was the Wild West of the Internet. Online, people could find (or steal) practically anything; the only real limitation was the atrocious internet speed. Newspapers eventually realized that advertisements were simply not going to generate enough revenue to keep operating, especially with the proliferation of the aforementioned scourge of the media industry: ad blockers.

As ad blockers became more common, the paywall was born. They pop up in all forms of media. Netflix paywalls movies. Audible paywalls books. And news sites paywall whatever insane thing a world leader had to say that day (any world leader, take your pick). Because of this global shift to housing all news and comms on the internet, people became more primed than ever to pay for subscriptions (and a lot of them).

Some news organizations found revenue in this subscription model (such as the Wall Street Journal), but many others continued to flounder and eventually shutter. As more and more media becomes subscription- and paywall-locked, consumers are beginning to push back on being nickel and dimed for every conceivable online service.

Membership and donation models (2010s–present)

Similar to the paywall, news agencies are beginning to play around and explore different donation models. This is more common in smaller publications with loyal readerships or within nonprofit industries. Additionally, writers and journalists are starting to paywall their own content and thought leadership through newsletters and services like Substack and Patreon.

Consumers are less likely to receive their media from traditional sources, even when those sources can be accessed online, than in the past. A recent Pew Research study found that people are slowly but surely turning to search engines, social media, and podcasts to get their news over dedicated news sites and apps. While news sites and apps are still the primary go-to, they’re increasingly losing their lead to social media, podcasts, and other forms of microblogging.

Additionally, revenue for news services is dropping almost across the board. Few newspapers have been able to successfully maintain (or even grow) in this current news business climate. Newspaper revenue overall has dropped over 15% just since 2017, and the industry doesn’t seem to be doing much to adapt.

The elephant in the room: owners, private donors, and interests

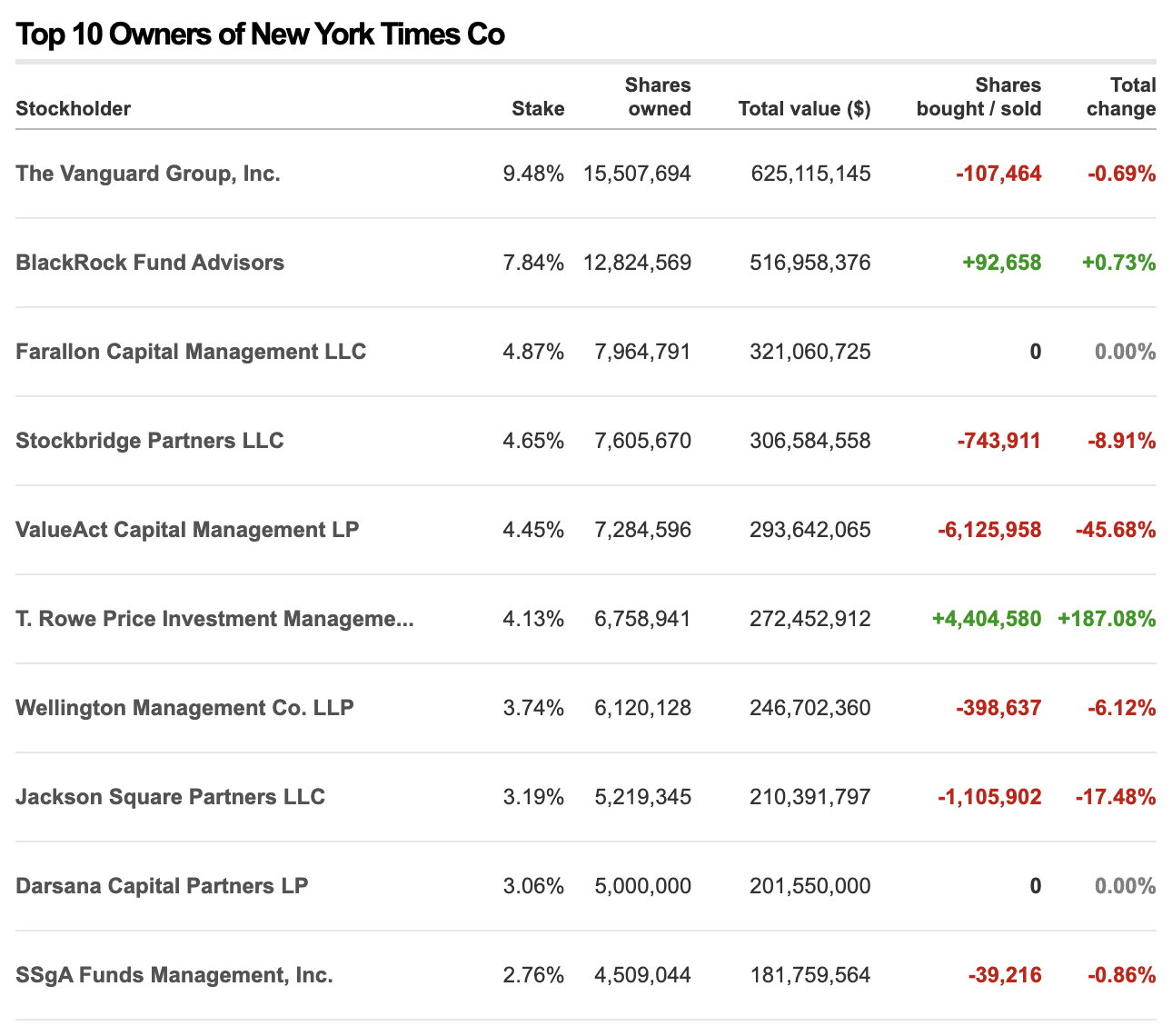

Up to this point, we've discussed how newspapers fund themselves. But this is only part of a bigger picture. You can’t realistically talk about media monetisation without discussing the impacts that revenue sources have on what gets discussed and why.

Private donors, partisan groups, government entities, and lobbyists have political and social stakes in what news gets covered and how. Even advertisers often have strong, vested interest in what gets discussed and what doesn't. It's hard to be entirely unbiased when your next paycheck comes from a company that doesn't want you to run a particular story or tell us a specific narrative.

.png)

To be a mindful media consumer, you must know who funds your media and why. Media consolidation has massive implications for partiality and contributes significantly to corporate interest interference and biased reporting.

Some good resources for analyzing media bias and ownership:

- AllSides Media Bias Chart

- Media Bias Fact Check

- Who Owns Your News? The Top 100 Digital News Outlets and Their Ownership

- Ground News

This was the first article in the series where I will analyze the objectively broken media monetisation system. Next, we will discuss alternative media monetisation models. If you have any thoughts, reach out to me on Twitter/X. I’d love to hear them.